The newly published book by Cato Senior Fellow George Selgin, False Dawn: The New Deal and the Promise of Recovery, 1933–1947, is a definitive history of the United States’ recovery from the Great Depression—and the New Deal’s true part in it. False Dawn is “an extraordinary achievement,” says economic historian Robert Higgs. “Economists, historians, and others have been researching the New Deal’s recovery programs and policies since the 1930s, but no one has ever done so as comprehensively and astutely as Selgin.” A portion of the new book, published by the University of Chicago Press, is excerpted below. To buy the book, click here, here, or here.

(Reprinted with permission from False Dawn by George Selgin, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2025 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.)

Chapter 26, The Great Rapprochement

What finally ended the Great Depression? We’ve seen that whatever it was, it took place not during the 1930s but sometime between then and the end of World War II, when a remarkable postwar revival occurred instead of the renewed depression many feared. We’ve also seen that while postwar fiscal and monetary policies weren’t austere to the point of preventing that revival, they alone can’t explain it, because they can’t explain the reawakening of private business investment from its slumber that lasted for a decade and a half.

…

Freed Enterprise

America’s involvement in World War II completed this process of regime change. It did so first by causing the Roosevelt administration to renounce its plans for radical economic reform, and then by convincing many that reports of capitalism’s decrepitude had been premature.

Even before the United States entered the conflict, World War II had added a fourth R—rearmament—to the New Deal triad of relief, recovery, and reform, and it did not take long for that upstart R to start shoving the original three aside. By putting many formerly unemployed Americans to work, rearmament rendered New Deal relief and recovery efforts otiose, at least temporarily. And conservatives in Congress, if not the New Dealers themselves, were convinced that rearming either Europe or the United States and doing so quickly meant putting New Deal reform efforts on hold. “The conservative bloc forged during the New Deal era,” Charlie Witham (2016, 22) observes, “reminded Roosevelt that there would be no question of the nation’s defense being provided by anything other than private enterprise: there was no suggestion of nationalizing industries as in Europe. Rather, federal censure of big business was relaxed as corporations were enticed to switch to war production.”

It appears as well that after Pearl Harbor Roosevelt no longer needed much convincing. Despite having long vilified American businessmen, he couldn’t possibly achieve his ambitious rearmament goals, including fulfilling his promise to get sixty thousand warplanes built in 1942, without their cooperation. He also understood “that businessmen would respond more readily to direction from other businessmen than to orders from what they considered a hostile federal government” (Brinkley 1995,190; see also Herman 2012,119).

Businessmen thus came to play important roles in the federal government itself, often as heads of newly established government departments (Witham 2016, 22, 60). Whereas over the course of the New Deal “the economic headquarters of the country had … moved from Wall Street to Washington;’ so that “no major decision could any longer be made in Wall Street without the question being asked, ‘What will Washington say to this?”‘ (Allen 1940, 218), Wall Steet now began taking over Washington. “By mid-1942,” Brinkley (1995, 190) observes, “over ten thousand business executives (most of them Republicans) had moved into offices, cubicles, and even converted bathrooms in the hopelessly overcrowded headquarters of the war agencies.” At first these businessmen-bureaucrats, many of them “dollar-a-year” men whose real salaries continued to be paid by their old companies, “had to confront New Dealers who opposed their role and suspected their motives” (Herman 2012, 54). But their growing numbers soon “shifted the balance of influence within key departments away from those with low, New Deal assumptions about business toward a more pro-business outlook’’ (60).

As businessmen filed into Washington, many of the New Deal’s heavy hitters filed out. A year after Pearl Harbor, hardly any were left (Brinkley 1995, 145). Of the biggest guns, Harry Hopkins, Henry Wallace, and Harold Ickes alone remained. But businessmen no longer had much reason to fear Hopkins, who tried to patch things up with them after he became secretary of commerce in December 1938.1 They had even less to fear when he went to London to serve as Roosevelt’s personal emissary to Winston Churchill. Wallace, upon becoming vice president, was assigned to various war mobilization boards, where he tried pitting his not-so-business-friendly mobilization philosophy against Jesse Jones’s, and lost. Later, as secretary of commerce, Wallace “made no significant reforms and chose conservative businessmen for his top aids” (Macdonald 1947, 36). Ickes, who had taken “a sadistic delight in needling businessmen’’ (Cady 1981, 162) and considered handing control of government agencies to them “an affront to Democracy” (Herman 2012, 72), thus found himself isolated and impotent (Brinkley 1995, 145). And his loneliness can only have increased after the 1942 election sent fifty-three former Democratic representatives—eight Senators and forty-five congressmen packing.

So, what began as a temporary expedient ultimately resulted in a permanent shift in government policy from high-handed interference with business, especially big business, to indulging it.2 …

Capitalism, After All

As the war dragged on, many New Dealers themselves discovered, in working alongside businessmen, that they “did not always have horns” after all (Brinkley 1995, 173). Nor could the New Dealers deny the war industries’ impressive achievements: “No other wartime economy,” Arthur Herman (2012, 255) observes, “depended more on free enterprise incentives than America’s, and … none produced more of everything in quality and quantity, both in military and civilian goods.” Although the government let loose the reins on private enterprise and relied, for the most part, on carrots rather than sticks to persuade it to produce war materiel, the United States produced more military supplies than all the other combatants combined and did so with the least sacrifice of consumer goods output, even making allowances for exaggerated wartime output statistics. Even in 1944, when 70 percent of US manufacturing was being devoted to winning the war, more than half of all US businesses, including several major military contractors, were still making consumer goods. In this respect, the United States was the least mobilized of all World War II belligerents (335–36).

It’s no wonder, then, that many liberals who once considered businessmen their bitter enemies were now ready to bury the hatchet. “The capitalism that had been damned as bankrupt just a few years before,” Robert Collins (1981,81) writes, “was now celebrated for its prodigious feats of production.” The war thus “muted liberal hostility to capitalism and the corporate world,” diverting liberals’ efforts into less confrontational channels (7).

This change of attitude was evident in politicians’ rhetoric as well as in actual policies. According to Collins (1981,80–81), “the attacks on business—both actual and rhetorical—of the late 1930s petered out,” giving businessmen “a welcome respite from the tensions of the Depression and the New Deal.” “By 1945,” Alan Brinkley (1995, 6–7) says, “the critique of modern capitalism that had been so important in the early 1930s … was largely gone, or at least so attenuated as to be of little more than rhetorical significance.”

Ickes, admittedly, was having none of it. Instead of seeing the US economy’s wartime experience as proof that capitalism was alive and kicking, he thought it demonstrated the merits of National Recovery Administration-type corporatist planning. He thus imagined that the war would deal the coup de grace to the idea that government “should rely upon private enterprise and individual initiative to invent and develop.” But hardly anyone else thought so. “What is striking,” Mark Wilson (2016, 183–84) says, “is how little traction [Ickes’s] perspective had during the reconversion period and longer Cold War era.” American policymakers instead drew a conclusion precisely opposite Ickes’s, as did businessmen generally. So far as they were concerned, “the fifteen-year debate over the health of U.S. capitalism had … been settled in favor of private enterprise” (Witham 2016, 60). Paul Koitsinen (1973,478) puts it bluntly: “With the conclusion of hostilities, New Deal liberal ideology had been undermined.”

Besides appearing to demonstrate the merits of capitalism, the war gave a bad odor to anything that smacked of fascism, including the activist managerial state. Between them, Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia, the Spanish Civil War, and the rise and crimes of Hitler forever laid to rest the “cautious admiration for Mussolini” and corporatism that many New Dealers once expressed (Brinkley 1995, 155, see also Whitman 1991). The Cold War in turn put left-wing interventionists on the defensive. As a result of both wars, Alan Brinkley (1995, 155) observes, Americans not only saw “autocracy as the greatest threat to democracy and peace.” They also came to see the United States as “admirable above all for not being a totalitarian state.” And not being a totalitarian state meant rejecting both fascism and socialism in favor of something closer to free enterprise.

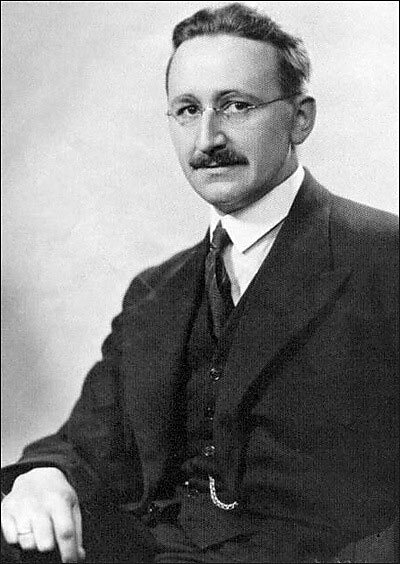

Nor was there a lack of support for the genuine free enterprise article. Several postwar anti-totalitarian writings, above all Friedrich Hayek’s (1944) The Road to Serfdom, treated the interventionist state not as a desirable compromise between totalitarianism and laissez-faire but instead as a malignant tumor that threatened to metastasize into full-blown totalitarianism, casting it in the role New Dealers once assigned to large, inadequately regulated corporations. Works such as Hayek’s didn’t just appeal to conservatives and libertarians. Among American liberals, they reinvigorated “a powerful strain of Jeffersonian anti-statism … that had been present all along” (Brinkley 1995,160 ). Hayek’s book itself also impressed at least one very prominent European liberal. After reading The Road to Serfdom on his way to the 1945 Bretton Woods Conference, Keynes wrote to Hayek from a New Jersey hotel, calling it “a grand book’’ and declaring himself “in agreement with virtually the whole of it; and not only in agreement with it, but in a deeply moved agreement.”

Although Keynes and Hayek are usually regarded as poles apart, with Keynes serving as the principal bete noire of capitalism’s champions, viewed against the background of the New Deal’s more heavy-handed efforts, let alone against that of outright fascism, socialism, and communism, they had much in common. Both men considered themselves liberals, and both preferred capitalism to any sort of totalitarianism. Setting aside a recondite (albeit bitter) dispute about the role of saving on one hand and monetary expansion on the other in either causing or combating business cycles (Kurz 2019; White 2012, 137–41), the difference between them, though far from trivial, was in an important respect one of degree rather than in kind. It’s true, of course, that Keynes, in supposing that “those carrying it out” would be “rightly oriented in their own minds and hearts,” was far less wary of government planning than Hayek, who believed instead that “the worst get on top” (White 2012, 171–72). But unlike many of his other contemporaries, including die-hard American New Dealers, Keynes was, in the British academic argot of the time, a “Thermostater” rather than a “Gosplanner”: he favored having the government contribute to and manage aggregate demand, especially by making up for slack private investment, but he was not keen on all-around government planning (Singh 2009, 371).

… Keynes wanted to inject a limited amount of what they both called ‘planning’ into the economy to protect the patient from its virulent form. Hayek claimed that Keynes’s vaccine was bound to bring on the full-blown disease. Keynes in turn thought that Hayek’s intransigent resistance to any encroachment on market allocation was likely to bring on the very evils it claimed to prevent.” In truth, both Hayek and Keynes played their part in the postwar capitalist revival, and it is only because that revival took place that they can now be cast, in textbooks, monographs, and humorous videos, as extreme antagonists (Wapshott 2011; Emergent Order 2010).

Spontaneous Optimism

… When economists today say that World War II ended the Great Depression, most have in mind the consequences of massive wartime spending, not the government-business detente the war inspired. Yet that detente ultimately mattered more, for it endured, whereas the spending didn’t. That detente is what made possible the rallying of animal spirits that was crucial to the postwar investment boom. “Conventional wisdom has it,” Gary Best (1991, 222) observes, “that the massive government spending of World War II finally brought a Keynesian recovery from the depression.” However, Best continues, the fact that the government was no longer at war with business, as it had been during the original New Deal, deserves more credit. “That,” Best says, “and not the emphasis on spending alone, is the lesson that needs to be learned:’ 3

Yet Another New Deal?

“By 1945,” Alan Brinkley (1995, 269) says, ‘‘American liberals … had reached an accommodation with modern capitalism .…

Postwar liberals were “less inclined to challenge corporate behavior [and] more reconciled to the existing structure of the economy.” Nor were they keen on “controlling or punishing ‘plutocrats’ and ‘economic royalists; an impulse central to the New Deal rhetoric of the mid-1930s .… ‘Planning’ now meant an Olympian manipulation of macroeconomic levers, not direct intervention in the day-to-day affairs of the corporate world” (Brinkley 1995, 7). Keynesian thinking clearly contributed to this change. But such thinking is properly seen not as a continuation of the New Deal but as an alternative to it.

…

This isn’t to say that the New Deal, properly understood, contributed nothing to postwar stability and growth. First and most importantly, New Dealers managed—albeit with plenty of help from Herbert Hoover’s men—to put an end to the monetary crisis that had brought an already depressed US economy to its knees. For decades (not forever, alas), early New Deal reforms made bank runs rare while making banking crises appear to be a thing of the past. How long the Great Depression might have lasted had the banking situation not been stabilized is anyone’s guess. To the extent that they increased the size of government, New Deal reforms also reduced somewhat the US economy’s vulnerability to adverse changes in private investment, if only by sacrificing some long-run growth.

It remains true, nonetheless, that the Great Depression was still going strong when World War II broke out in Europe. Although recovery commenced once the banking crisis was resolved and the dollar’s gold anchor was weighed, it did so in fits and starts. Subsequent New Deal policies were mainly responsible for the fits. The partial recovery itself was mainly a result of the “gold rush’’ begun by devaluation and kept going by Hitler’s rise to power and the subsequent, rapidly growing odds of war.

To point these things out isn’t to condemn the New Deal root and branch, for as has been emphasized here again and again, economic recovery was not New Dealers’ only goal. Those wishing to celebrate the New Deal might do so, first of all, by pointing to any of its many longer-term achievements they consider worthwhile. They can also observe that the New Deal provided jobs to millions of otherwise unemployed Americans while helping many, through mortgage refinancing, to keep their homes and farms. And if those who celebrate the New Deal don’t mind letting Hoover appointees share some of the credit, they can claim that by resolving the banking crisis and loosening the dollar’s “golden fetters,” early New Deal actions ended the Great Contraction, thereby making recovery possible. But they cannot say, without contradicting a wealth of evidence, that most subsequent New Deal policies and rhetoric promoted recovery more than they hampered it.

The practical lesson to be drawn from our assessment of the New Deal’s bearing on recovery ought to be obvious enough. When the next severe downturn occurs, policymakers and other experts will once again cast about for ways out. Relying on conventional wisdom, many will be tempted to seek them among various New Deal undertakings. But if, as has been argued here, many New Deal policies held back recovery, while those that helped most—such as ensuring bank deposits and relaxing gold standard limits on monetary expansion—are as unrepeatable as losing one’s virginity, they’d be wiser to treat most of the New Deal episode as a warning about steps best avoided and to look elsewhere for better ones.